The Politics of ‘the Tiniest Things’: Oberhausen Short Film Festival 2016

Oberhausen, Germany, May 5 - 10

Juan A. Suárez

No longer the polemical window to the East European cinemas it once was, nor a showcase for protesting the complacencies of the German film industry—by the signers of the famous Manifesto in 1962 or by mavericks such as Hellmuth Costard, whose Besonders wertvoll (1968) featured a talking penis, explicit masturbation and farting to criticize the German Film Promotion Act of 1967—the Oberhausen Short Film Festival is by now a sedate if intellectually stimulating event. The different competitions (International, German, Children and Youth, music video, and North-Rhein Westphalia), the theme section, the distributors’ selections, the archive shows, the profiles, and occasional unaligned programs offer enough goods to fuel months of obsessive watching. The films are diverse enough in provenance, topics, style and technique that a general summation would court simplicity. The Festival’s web site, however, rounds up some traits that remain, in a way, the Oberhausen seal—“diverse, political, independent.” Diversity is apparent in the rising number of films from Asia, Africa, and Latin America in a competition once dominated by European and North American entries, yet far from a recent development, globalism is a long-standing trait of the festival. Independence signified, again in the festival’s website, the fading of Film Schools as main contexts for short film production, an assertion that would have to be somewhat qualified in view of the continuing presence of projects originating in La Fresnay or in Tokyo University of the Arts, to cite just two well-represented institutions. And “political,” an admittedly broad term, gestures at the variety of social and historical engagements which inform many of the films on the slate.

Politics—or more precisely, its fluid configurations and shifting locations, both in the present and the past—was certainly an overarching concern in this year’s International Competition, in the profile devoted to Chinese animator Sun Xun, and in the Theme—“El Pueblo: In Search of Contemporary Latin America—curated by Federico Windhausen and devoted to the changing articulation of “the people” as political agents and/or objects of representation in recent—mostly post-2000s—Latin American experimental film.

Many of the films in these programs seemed to orbit—whether they knew it or not—around a question from Chris Marker’s Sans soleil (1982): “Do we ever know where history is really made?” Marker’s film places it away from the official sites of power and closer to what might seem the trivialities of daily life: “. . . by learning to draw a sort of melancholy comfort from the contemplation of the tiniest things,” the film’s narrator says, a group of idling courtesans in eleventh-century Japan “left a mark on Japanese sensibility much deeper than the mediocre thundering of the politicians.” Like history, politics and social struggles often arise from and around “the tiniest things.” Do we ever know where politics is really made? The question seemed to provide the conceptual prompt to a significant number of titles, and opened a possible path for navigating the festival. For the sake of manageability, I will limit my commentary to the International Competition and the Theme section.

The answers were as varied as the geographical and historical scenarios explored by the films. Cumulatively, they demonstrated the atomization of the political and its percolation to the minutest recesses of the quotidian: to the intimacy of home and family, to children’s street games, to spells against evil eye and occupation forces, to inadvertent gestures at a political convention, to formal exercises with light and color, and—insistently—to the way we remember the past and live with its traces. This inventory of unsuspected political sites—taken from the films in the programs—recalls Walter Benjamin’s concern with the redeeming energies latent in the debris of the culture: in images, objects, and ephemeral practices. As he states in the very opening of One-Way Street, “The construction of life is at present far more in the power of facts than of convictions, and of such facts as have scarcely ever become the basis of convictions.” Facts, however, were not in Benjamin, nor in the films I am reviewing here, tokens of impregnable objectivity, but occasions for reflecting on the slippery, multi-sided nature of events. A forgotten historical episode, an urban location, a faded photograph, an intimate memory: they are all placed at the crossroads of the macro- and micro-political, the intimate and the public, personal and collective histories, and threaded through endless webs of mediation and refraction. Such epistemic relativism explains the staggering variety of voices, tones, and techniques across and within individual titles; relativism may also be the reason why hybridity has become a sort of norm, with quite a number of films combining small gauge film, digital processing, still photography, text, staged action, voice over, and found and composed sound. “There has [always] been an aesthetics of matters-of-fact, of objects, of Gegenstände,” recalls Bruno Latour as he vindicates the role of objects and materials in political processes. Politics and history are arrangements of images and sounds. And as many of the titles screened in Oberhausen this year remind us, it is through images and sounds that one-sided, univocal versions of politics and history are analyzed, revised, and undone so that other worlds, and other meanings, may be liberated in the process.

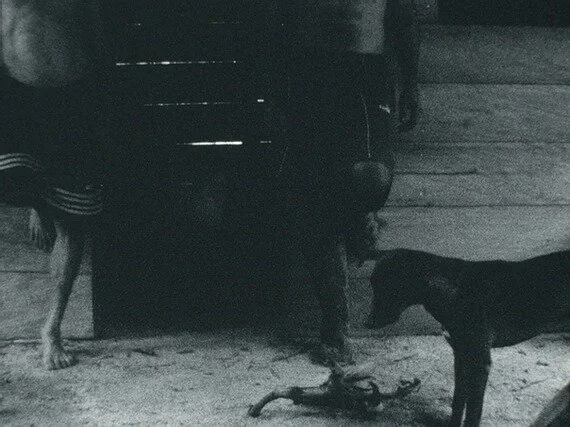

JUS SOLI (somebody nobody 2015)

Among the contents thus emancipated were unofficial histories of modernity—flip sides of various homogenizing projects, such as urban reform, economic progress, or the consolidation of the nation state. In Michelle Latimer’s Nimmikaage (She Dances for People) (Canada, 2015), an Inuit woman dances in a snowed-covered landscape; her image is cross-cut with shots of wildlife and of 1940s movie audiences and with a newsreel of the visit of a British royal parsonage to Canada—a succinct, poetic reminder of the way Native peoples have been collapsed with nature, turned into spectacles, and excluded from the genealogies of the nation. British collective somebody nobody (Simon Jenkins, Michael McLeod and Joshua Llewellyn) also mixes newsreels and staged performance in JUS SOLI (UK, 2015). Footage of West Indians disembarking in England in the 1950s evokes the promise of the new land, and contrasts with the racism and exclusion they encountered, emblematized in the film through the New Cross House fire of 1981 in which thirteen West Indian teenagers died in a blaze allegedly provoked by extreme right-wing militants. The tragic event is elliptically represented by the gradual crumbling to the floor of thirteen black youths in a darkened set; filmed in stark black and white, the scene contrasts with amiable English landscapes filmed in color that, in the context of the film, seem less bucolic than complicit with oppression. Less tragic than ambiguously elegiac is Darko Fritz’s Zagreb Confidential—Imaginary Futures (Croatia 2015); flickering through archival footage, models, old photographs, and computer animation, it recreates the expansion of the Croatian capital in the 1960s and 1970s with a mixture of wistfulness and irony. It laments the replacement of peasant dwellings and small orchards with rectilinear avenues and apartment buildings as well as the failure of modernization to provide a stable polity; the failure of modernization is foreshadowed in the footage of performances carried out in the 1970s by artist Tomislav Gotovac in the Utrina Market of the New Zagreb satirizing the illusory comforts of modernity. Federico Benevides and Yiri Firmeza’s Entretempos (Brazil 2016) is more aligned with Gotovac’s satire than with Fritz’s melancholia. Their film is another hybrid combining grainy early twentieth-century photographs, stop-motion animation, and computer graphics, all bathed in primitive Brazilian vocal music; it speedily tracks the spread of modern infrastructures—highways, high-rises, sports stadia—and the concomitant replacement of the warm, expressive crowds of old photographs with the robotic folk of today—rendered through deliberately crude digital graphics.

In other films the flip side of modernity is not its repressed, submerged histories or undelivered promises, but the shelters offered by intimacy or myth. The artisanal family industry recreated in Rajee Samarasinghe’s lyrical If I Were Any Further Away I’d Be Closer to Home (Sri Lanka, USA, 2016) is an example of the former, and Kristin Li’s animation Two Snakes (Canada 2015), of the latter. The personal realm is a space of autonomy in Ieva Epnere’s Four Edges of Pyramiden (Latvia 2015), whose protagonists carve a niche for themselves in a declining USSR mining site “at the end of the world”— the island of Spitzbergen. They imbue the island’s lunar landscape and inhospitable environment with biographical, mythic, and mystical significance. It is in part a beautifully photographed landscape film, which abundantly uses still images and long static takes, a fourfold portrait—the filmmaker’s grandmother is among the portrayed—and a reflection about living in the shadow of a modern ruin, since Pyramiden was in the 1960s and 1970s a model Soviet community.

The Day Before the End (Lav Diaz 2015)

Not intimacy or myth but literature provides shelter from the (literal) storm in Lav Diaz’s Ang awar bago ang wakas (The Day Before the End, Philippines 2015), winner of this year’s Principal Award and described by the jury as “a film of political urgency.” Characters recite Shakespeare’s words in different parts of a city about to be lashed by a severe tropical storm. After the storm, a butterfly in a non-descript interior provides, we are told in a subtitle, a counterpoint of “life” and “color”—the film, however, is in moody black and white. Color and life may be of a piece with the dramatic intensity provided by Shakespeare’s lines in the film’s indifferent urban milieu. If Diaz sets Shakespeare off against a dull everyday, soon to turn catastrophic, Laure Prouvost uses joyous play to escape the stringencies of the museum in If It Was (Great Britain 2015), doubly awarded by the regional Ministry for Family, Children, Youth, Culture and Sport and by the International Critics jury. The film combines digital graphics, found footage, staged action, and photographic negative. A dreamy, French-accented off-screen commentary fantasizes about the possibility of turning the museum, modern cathedral of culture, into a funhouse. It would be open at all hours and decorated in pink by grandmothers, and visitors would receive massages and would be encouraged to improve the paintings by adding boobs where they please “so people will look” at the art. Part of Prouvost’s installation “We Would Be Floating Away from the Dirty Past,” on view until September of 2016 at Munich’s Haus der Kunst, the pieces does not only suggest an escape from the museum as institution but, more concretely, from this particular museum’s history, created in 1937 as a showcase for Nazi art.

If It Was (Laure Prouvost 2015)

Other works, however, exposed the impossibility of finding refuge from the violence of history, whether this violence takes the form of political prosecution (Paz Encina’s Tristezas; Sorrows, Paraguay 2016), economic crisis (Omar Belkacemi’s Lmuj; The Wave, Algeria 2015) or all out war (in Belit Sag’s Eylül-Ekim 2015, Cizre; Sept.-Oct. 2015, Cizre, Netherlands 2015, a straightforward documentary of Turkish military repression in Kurdistan, or in William E. Jones’s A Great Way of Life, USA 2015, which collates footage of marines in Vietnam with sound bites from contemporaneous television advertisements). Two interesting reflections about the inexorability of history are Gonzalo Egurza’s Schuld (Argentina 2016) and Gabriela Golder‘s Tierra Quemada (Burnt Land, Argentina 2015). In Egurza’s Schuld a young Argentinean couple spends the worst years of Videla’s dictatorship traveling through Europe, sheltered from the country’s violence yet uncertain as to the ethical legitimacy of their escape. It is assembled from 8mm home movies and family photographs, accompanied by a meditative voice-over commentary, and punctuated by intertitles with quotes by Walter Benjamin and by clips from Ninotchka, Terra em transe, a CBS television debate from the early 1970s featuring Norman Mailer, and La fiesta de todos, a populist documentary on the Argentinean conquest of the 1978 soccer world cup. It is wistful, insightful, and merciless in its probing of the circuitous paths of guilt and complicity, yet at times also slightly mannered in presentation. In Golder’s Tierra Quemada (Burnt Land, Argentina 2015), intimacy is threatened by natural catastrophe in the form of the fortuitous fire that devoured several neighborhoods in Valparaiso in 2014, an event that may be easily read as an allegory for historical cataclysm. The film takes the form of a visual riddle: the white screen that opens the film turns out to be fog slowly lifting from a blackened landscape that only gradually acquires legible contours; in the soundtrack, children’s voices describe with touching naiveté the ferocity of the fire that destroyed their homes.

Elegance (Virpi Suutari 2015)

Politics is less demarcation—between private and public; official and unofficial history; sheltered and exposed—than style and embodiment in Pavel Medvedev’s Hubris (Russia 2015), Virpi Suutari’s Eleganssi (Elegance, Finland 2015), Anocha Suwichakornpong and Tulapop Saenjaroen’s Nightfall (Thailand, Singapur 2016), and Louise Botkay’s Mains propres (Washed Hands, Brazil 2015). By filming in close-up and medium shots the delegates of Russia’s ruling party during a convention, Medvedev offers a study of the brutal physiognomy of the powerful reminiscent in some ways of August Sander’s photographic taxonomy of early twentieth-century German society. In Suutari’s breathtakingly elegant Eleganssi, recipient of the Zonta prize to a woman filmmaker in the German or International Competitions, the potential violence of the social elites is displaced onto hunting partridge and pheasant—“a very emotional” affair, declares one of the hunters—and clad in the refinements of dog breeding, exquisite interiors, and haute cuisine. Suwichakornpong and Saenjaroen’s Nightfall point their camera lower in the social pyramid to explore the corporeal registers of the governed: the listlessness, anomie, and fatigue of a middle-aged woman who traverses impersonal spaces in Singapur while political speeches in the soundtrack trumpet the country’s economic splendor. In turn, Botkay’s Mains propres, awarded the e-flux Prize, explores the contrasting body languages of the powerful and the powerless. International cooperants in sub-Saharian Africa, whose stares and postures communicate their privilege, are contrasted to local dwellers, who adopt, as if on cue, their expected look of despondency. A harrowing scene shows a group of mothers and their babies being subjected to a grotesque photo-call by cooperants in search of the perfect snapshot of misery; but the women’s collective laughter, once left alone, reveals their ironic understanding of the spectacle in which they are forced to play a part.

Monuments give political gesture a permanent shape and index a relationship to the past that is inevitably mediated by present interests and commitments. Dimitri Venkov’s Krisis (Crisis, Russia 2016) dramatizes a facebook discussion among Russian and Ukranian artists about the demolition of a statue of Lenin in Kiev; the exchange operates as a barometer of present alliances and discords. Similarly, Sirah Foighel Brutmann and Eitan Efrat’s Orientation (Belgium 2015) reflects on the way a monument to the city of Tel-Aviv contributes to erasing a Palestinian landmark—an illustration of how the past is edited to enforce a univocal conception of the present. Deimantas Narkevicius’s 20 Juli. 2015 (Lithuania 2016), which received a special mention, describes the removal of a Socialist monument—an allegory to the peasantry—from a bridge in Vilnius. The film’s focus is the ebb and flow of urban life around the stiff statuary and the attempts of news crews and a young filmmaker to capture the scene. This last repeatedly (and humorously) claps his hands in front of the camera to synchronize the take. Close-ups of cracks, rust, and moss on the monument suggest the ephemerality of history and its reversion to natural and geological time. The demilitarized zone between North and South Korea is less a monument than an open wound between two worlds. Hayoun Kwon’s adroit digital animation 489 Years (France 2016), distinguished with awards from the Ecumenical Jury and from the Rhine-Westphalia’s Ministry for Family, Children, Youth, Culture and Sport, proposes a ride through the area, which, according to the testimony of a former South Korean soldier heard on the soundtrack, is both deadly and enchanted. It is an unusual mixture of denunciation (the title refers to the time it will take for the landmines in the area to become deactivated), magical realism, and immersive computer game aesthetics.

489 Years (Hayoun Kwon 2015)

Naturally, not everything in the international competition had political resonance. In fact, my narrative leaves out some remarkable titles with entirely other concerns. Louise Carrin’s Venusia (Switzerland 2015), Winner of the Grand Prize of the City of Oberhausen, is a study of a subtly abusive friendship between the owner of a brothel and her lazy Albanian employee, whose charming malingering forces the former to start taking clients again. Presented as a documentary of these women chatting, filing their nails, answering the phone and generally languishing in slightly varying frontal frames, it is impeccably paced and suffused with a mild hilarity reminiscent of the best Jarmusch. And Ohtakara Hitomi’s Omokagetayuta (Calling You, Japan, 2016), is a delicate, beautiful homage to a missing mother; it mixes animation, digital video, and abstraction, and features a pulsing, viscous blob that creeps around the house as a remainder of the departed.

While in the International Competition the insistence on politics and history may be read symptomatically—as an epochal concern—in the Theme section, it was explored systematically. As Theme curator Federico Windhausen states in the catalog essay, the section’s title (“El Pueblo”) evokes the various meanings of the term in Spanish, from particularizing and local—the village—to abstract and agglutinative—the common folk, the people as a cultural-national unity, or as autonomous political agents. In these last senses, el pueblo was the protagonist of the classic militant cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. Yet from the late 1970s onwards, “the people” as a unified, homogenizing entity appeared increasingly unwarranted given rising awareness of the role of (gender, class, ethnic, sexual, national) difference in social formations and the widespread skepticism, in philosophy and political theory, about totalizing narratives—including narratives of emancipation in which the people featured prominently.

Omokagetayuta (Calling You) (Ohtakara Hitomi 2016)

Stripped of its totalizing claims, however, the concept remains generative in Latin American culture, as Windhausen and critics and theorists Sebastián López (independent curator, Amsterdam), Gonzalo Aguilar (University of Buenos Aires), and Vinicius Navarro (Emerson College, Boston), convened in the Podium discussion “Borders of the Regional.” The people may be regarded—Aguilar’s words— “a gap” or an “ellipsis”: the missing place of a political actor either absent or about to arrive yet never quite in place; or, in the views of López, Navarro, and Windhausen, a contingent, atomistic entity whose outline changes in relation to specific struggles and contexts.

The Theme programs set out to explore the way such variability was reflected in recent Latin American artist’s film, characterized, once again in Windhausen’s view, by a return to the social. The terms of this return naturally differ from those of classic militant films. Recent works are less “polemical and agitative” than interrogative and tentative; less panoramic than “microscopic and fragmented”; and, in Vinicius Navarro’s terms, less “didactic” than “dialogic.” They are also resolutely hybrid, ranging across the testimonial, the staged performance, various documentary modes, elusive storytelling, and formalist exercises, with several titles combining many of these approaches. However, the overarching genre to which most films belong in one way or another is the essay—an omnivorous mode that, in Timothy Corrigan’s recent characterization, bridges the subjective and the objective, the personal and the political, while foregrounding—when not questioning and relativizing—its modes of enunciation. The fractal border zone between the personal and the political was the focus of all the Theme’s selections—a borderline on which alternative figurations of the people and the popular emerge, and along which the affordances and limitations of emancipating action are revealed.

The originality of the programs stemmed in part from their eschewing the most obvious genealogies of Latin American political cinema—the influence of Birri, Sanjinés, Solanas-Getino, Gerardo Vallejo, Santiago Álvarez, and the Brazilian cinema da rúa, among others, in shaping later styles of engagement—in favor of more subterranean networks and lines of influence, more suitable to contemporary figurations of the political. Two programs included the work of US filmmakers Bruce Baillie (Valentín de las Sierras 1967) and Chick Strand (Fake Fruit Factory 1986), titles that found considerable echo among Latin American filmmakers seeking for alternatives to the traditional documentary. Their inclusion indicates an expanded idea of the “Regional” that takes into account trans-continental exchange and the centrality of travel, migration and exile. These forms of displacement characterize the lives and careers of Gianfranco Annichini, Teo Hernández, and Marielouise Alemann; often neglected in histories of Latin American cinema, they were included in the program “The Outsider In,” on geographical and social marginality. Italian-born and raised in Switzerland, Annichini has been, since the end of the 1960s, an influential presence in Peruvian cinema. His Radio Belén (Peru 1983) depicts an impoverished neighborhood in Iquitos pervaded by the sounds of a radio station that broadcasts its contents through loudspeakers rather than through radio frequencies. Teo Hernández was born in Mexico but resided in Paris during most of his adult life. His astonishing Trois gouttes de mezcal dans une coupe de champaigne (France 1983) hovers between abstraction and concreteness, while the voice-over commentary offers a blend of family history, sentimental confession, and meta-cinematic conceit. And born in Germany but relocated to Buenos Aires in childhood, Marie Louise Alemann developed an intriguing but scarcely known body of work in the 1970s and 1980s, often in collaboration with Narcisa Hirsch. Her Umbrales (Thresholds, Argentina 1980) was filmed in Buenos Aires and Paris. It shows in grainy super-8 the agitated passage of a group of young men through a maze of rooms, stairways, courtyards, and hallways in what might be a circular search without goal. Its oneiric quality makes it a late-day descendant of the surreal psychodramas of the 1940s and 1950s, while its powerful homoeroticism—in many ways it is a stylized gay cruising film—is a shocking defiance to the military dictatorship then in power in Argentina.

La estancia (Federico Adorno 2013)

The open queerness of Umbrales reveals the expanded conception of the political animating the Theme programs. While some films adhered to militant subject matter, often rendered in unfamiliar idioms, the majority of the entries delved into traditionally non-militant arenas. The program “Theater of Conflict” was the most conventionally political. It showed the clash of public protest and state repression in conventional documentaries (Somos +; We Are More, Chile 1985); in the digital dispatches of MAFI-Mapa Fílmico de un país (A Country’s Filmic Map, Chile 2014); and in the conceptually compact and visually arresting shorts of the Mexican collective Los ingrávidos. Included in a different program—“From Passage to Chronicle”—Federico Adorno and Beatriz Santiago Muñoz portrayed popular struggles from unusual angles: Adorno’s La estancia (The Ranch, Paraguay 2013) recreated a massacre of indigenous peasants through enigmatic tableau vivants; and Santiago Muñoz’s La cabeza mató a todos (Puerto Rico 2014) fused indigenous magic and protest by showing a woman dancing in the dark while casting a spell against US war technologies. Conflict and resistance are more sublimated in Jose Luis Bongore’s Nariño (Colombia 2013) and Guillermo Moncayo’s Echo Chamber (Colombia 2014). The background to Bongore’s Nariño is the four-way armed conflict between guerrillas, paramilitaries, illegal gold prospectors, and drug traffickers in some areas of Southern Colombia; the film, however, centers on the healing from this multisided violence and in the sparks of hope contained in children’s games, in performances arising from theatrical workshops with local survivors, in a town’s festivities, and in the vivid colors of the landscape. In Guillermo Moncayo’s beautifully photographed Echo Chamber, the liquidation of Colombia’s rural railroad network leaves behind ruined stations and depots, and threatens the use of the railways as a means of social cohesion and a pathway to an intimate connection with the land. The films in the program “Labor is Absence” bypass conventional Marxist notions of class and alienation and delve instead on women’s affective networks and solidarity (in Nicolás Pereda’s El Palacio, Mexico 2013 and Chick Strand’s Fake Fruit Factory), on the oppressiveness of bureaucracy (in Néstor Siré’s Superación, Cuba 2012), and on new forms of labor surveillance in high tech industries (in Jorge Scobell’s chilling, trenchant, and hypnotic RH Reporte, Mexico 2013).

R H Report (Jorge Scobell 2014)

Most films, however, explored the political resonances of traditionally non- (or para-) political spheres such as sexuality and affect, the uses of urban space, (anti-)ethnographic encounters, and the performance of the self. All these experiential registers are mediated through the body, and are also sites where the body becomes traversed by social and political energies that render it heteronomous and unequal to itself. The confrontation with urban space was explored, with slightly different emphases, on two programs that dwelled on the gap between the city’s official and unofficial histories; and between its hardware—monuments, lay-out, infra-structures—and its soft-ware—the wayward actions that citizens perform on it. One of these actions is transit: a passage that personalizes the city and uncovers in it unaccustomed corners and perspectives. This was the focus of the program “The Film-Maker as Urbanist,” which insightfully repositioned Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo’s Agarrando pueblo (Vampires of Misery, Colombia 1975), a satire of social cinema’s pornography of poverty, as a city film. Azucena Losana’s Super-8 SP and Paolo Mazzolo’s Fotooxidación (Photooxidation, Argentina 2013) propose abstract journeys through Sâo Paulo and Buenos Aires, respectively; Mazzolo’s extraordinary work contains, in addition, a meditation on light. In Marco Bertoni’s Cocô Preto (Black Turd, Brazil 2003), the city is more background than topic; the invasion of alien Black Turd (its shadow was cast live on the screen by the filmmaker, who was running the projector) turns the urban landscape into a theater of campy horror—largely thanks to scenes appropriated from other films.

E (Helena Grama Ungaretti, Miguel Ramos and Walter Wahrhftig 2014)

If the cinema is a technology of urban transit, it is also a medium for the discovery of the city’s submerged histories and uses. The program “The City Machine” uses Brasilia as a case study of the gap between the city’s abstract design and its actual life—or between what Michel de Certeau famously called the concept city and the city of experience. The program rescued Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s Brasilia, contradicôes de uma cidade nova (Brasilia, Contradictions of a New City, Brazil 1967), a document of the early life of the city and the inequalities that grew on its margins. Clara Ianni’s Forma Livre (Free Form, 2013) revisits the massacre caused by the brutal repression of a strike during the building of the city. While Brasilia’s designers Oscar Niemeyer and Lucio Costa deny knowledge of the event in an audio recording, Costa’s designs and Marcel Gautherot’s photographs of the city’s construction are shown on the screen, along with images of the early decay of some of the modernist structures. Collective Corpos Informáticos’s Faixa de pedestres (Pedestrian Crossing, Brazil 2014) records a performance consisting in laying down a portable crosswalk—white stripes on asphalt-dark cloth—in several areas of Brasilia in order to stop traffic. Other works contest the abstract city of planners and designers in more elegiac tones. Cristian Silva-Avária’s evocative Mind the Gap (Brazil, Germany, Chile 2014) compares notions of time among Brazilian fishermen and German commuters, pondering at the same time the deleterious effect of speed and networks on social relations. Helena Grama Ungaretti, Miguel Ramos and Walter Wahrhftig’s E (Brazil 2014) wittily reflects on the privatization of Sâo Paulo’s public space through traffic, which in turn forces the conversion of spaces of memory and sociability into parking lots and garages.

Amor e outras construcôes (Gustavo Vinagre 2013)

Gustavo Vinagre’s hilarious Amor e outras construçôes (Love and Other Constructions, Brazil 2013) is as much a queer contestation of the city—three boys make out and have sex in construction sites and brand new housing developments—as an exercise in queer visibility. Other openly queer titles are Vinagre’s Filme para poeta cego (Film for a Blind Poet, Brazil, Cuba 2012), a portrait of gay sadomasochistic poet Glauco Mattoso that mixes interviews with some restaging of his foot fetish and bondage scenarios, and René Guerra’s Quem tem medo de Cris Negâo? (Who’s Afraid of Cris Negâo, Brazil 2012), a portrait of the eponymous Negâo—a violent black transvestite prostitute—put together from the conflicting testimonies of several other comrades in the street trade. Along with other titles such as Luis Sens’s Hotel Punta de Este (Argentina 2015) and Azucena Losana’s El guaraches (Leather Sandals, Mexico 2013), these portraits embed the self in broader social codes—of heterodox sexuality, upper-class elitism or working-class identity. They are representations of the kinds of differences that hinder the homogeneity of the pueblo and make this concept, at best, an articulation of social microcosms between which communication and coordinated action might be more or less possible.

Tropic Pocket (Camilo Restrepo 2011)

Communication between incommensurable worlds is the subject of the program “Against Ethnography,” which explores the encounter with indigenous realities. These run from the pre-Columbian cave paintings and contemporary inhabitants in a Peruvian mining region (Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s Contornos; Contours, Peru 2014), to victims of Maoist guerrillas in Peru (Vicente Cueto’s Raccaya Umasi, Peru 2011), to natives from northern Argentina relocated to Berlin to take part in a performance (Leticia Obeid’s Bilingüe; Bilingual, Argentina, Germany 2013), to tribes in the upper Amazon who fly airplanes and videotape their visits to neighboring communities. Camilo Restrepo’s Tropic Pocket (Colombia, France 2011) departs from the traditional ethnographic scenario to recreate, using different visual and aural languages, the impenetrable region of El Chocó, in northwestern Colombia. Videos uploaded to the web by guerrillas, fragments of documentaries by missionaries, excerpts from a US car advertisement, and footage of local dwellers filmed by Restrepo render a deliberately partial, complex, and elusive image of the area. This is recreated more as a cumulus of visual and acoustic traces (these include bird song and electronic reggetón dance music) than as a conceptually intelligible, neatly packed whole. Yet the moments of opacity and incommunicability that punctuate these films are not signs of complete failure. It is always possible to establish some sort of contact. The teacher-guide in Garrido-Lecca’s Contornos conveys, in a sensitive, humorous way, much nuanced information about the archeological site he is explaining. And Leticia Obeid, in Bilingüe, meets the Wichí on their own terms in their lands and starts to learn their language, in contrast with an Argentinean war veteran who visits their territory to hector them into embracing the flag and the national spirit.

Bilingual (Leticia Obeid 2013)

Ultimately, the provisional, fragile contact depicted in these anti-ethnographies may be seen as an allegory of the way the films I have been discussing approach historical and political realities. It is an approach aware of its own biases and partialities, and conscious of the inapprehensible kernel in history’s blind necessities. A kindred awareness of partiality and limits also informed the design of the Theme. Broad and historically deep, it is authoritative but never authoritarian. Windhausen described it as “probing and speculative,” with thematic “lines” and textual “clusters” that align the similar alongside “illuminating contrasts.” Individual titles could have been linked otherwise and other lines of inquiry might have been chosen. As it was, however, the Theme offered a necessary, unusual, and compelling picture of recent Latin American moving image cultures. This picture shows their dynamism, regional singularity, and intricate genealogies, but also their convergence with other traditions, similarly concerned with new political styles, new locations for action, protest, and resistance, and new social agents—new pueblos. Such convergence, which I have been tracking in this review, may result from the internationalism of experimental moving image cultures in the present. It also has to do with a universally embattled present in which conventional politics have been globally rebutted, popular revolt battles conservative retrenchment, and the impossibility—the uselessness—of proceeding with (social) life as usual is as sharply felt as the scarcity of roadmaps for moving ahead. Of course, contemporary experimental film cannot provide conclusive directions, but it can at least direct our gaze towards the “tiniest things” from which, as Marker influentially proposed and the films I have been reviewing insistently demonstrate, history and politics are mostly made.

Juan A. Suárez teaches American Studies at the University of Murcia, in Spain. He is the author of the books Bike Boys, Drag Queens, and Superstars (1996), Pop Modernism: Noise and the Reinvention of the Everyday (2007), and Jim Jarmusch (2007), and an associate editor of the “Cinema and Modernism” section of Routledge’s on-line Encyclopedia of Modernism. He has published numerous essays on modernist literature and experimental film in Spanish and English. Recent work in English has appeared in Grey Room, ExitBook, Criticism, and Screen, and in the edited collections Film Analysis, 2nd. Ed., eds. J. Geiger and R. L. Rutsky (W. W. Norton, 2013), Birds of Paradise: Costume as Cinematic Spectacle, ed. Marketa Uhlirova (Walther Koenig, 2014), and The Modernist World, eds. Lindgren and Ross (Routledge, 2015), among others. He has curated film programs for CCCB, Tate Modern, Museum Reina Sofía, and MOCA-LA-Pacific Film Archive. He is currently writing a book on experimental film and queer materiality.