In a State of Grace

Review of the 6th Annual FIDADOC

Sally Shafto

Things are there, why manipulate them.

- Roberto Rosselini -

Non-fiction film-making is the most interesting space

for creation in the Arab world today.

- Rasha Salti -

When does a documentary become cinema? It does so when it becomes bigger than its subject and takes on a universal dimension. It’s the human condition that interests me.

- Nicolas Philibert -

Morocco’s first and only film festival devoted entirely to documentary films, the Festival international du documentaire d’Agadir (FIDADOC), just ended its 6th edition (April 28 – May 4, 2014). It was a reInsounding success. Organized by the Association de Culture et d’Education par l’Audiovisuel, the festival was founded in 2008 by Nouzha Drissi who tragically died in a 2011 car accident in Casablanca. Today, her legacy is continued by FIDADOC’s President Hind Saïh and the Délégué Général, Hicham Falah, in partnership with the Moroccan television channel 2M that features Reda Benjelloun’s noteworthy program of documentaries (“Des histoires et des hommes”).

Reda Benjelloun awards the 2 – M Prize to Moroccan Filmmaker Dalida Ennadre for her film, Walls and People

FIDADOC President, Hind Saïh, just before the Closing Ceremony. Photo Credit: S. Shafto

This year, 35 films, included all together in the in-competition selection, a panorama, the Carte blanches, etc., paid tribute to the current effervescence in documentary filmmaking around the world. Positioning itself as a platform for exchange between the South and the North, the FIDADOC has become a must-attend event for documentary aficionados. What distinguishes this festival, besides the high quality of its programming, is its atmosphere of intimate conviviality in the tourist-popular city of Agadir on the Atlantic coast. (What a relief to escape the already rising temperatures of Ouarzazate for a week!) The well-known documentary filmmaker, Nicolas Philibert, one of this year’s honorees, said it best at the closing ceremony:

“There were, he told us, films to see but not too many, and people to meet but not too many: the FIDADOC is a festival on a human-scale.”

Another special feature of the FIDADOC is its emphasis on developing the documentary genre among young Moroccans. Around fifty film students from all over Morocco attended, while fifteen submitted professional projects for development. This year five students from the Faculté Polydisciplinaire de Ouarzazate accompanied me to the FIDADOC.

Nicolas Philbert with Amine, Hakim, Essam, and Mohamed-Amine. Photo: S. Shafto

Jean-Luc Cohen Confers with Mohamed-Amine and Manal about their film project on the steps of the Institut français. Photo: S. Shafto

Situating itself within the AFRIDADOC network promoting documentary film in Africa, the FIDADOC also marked this year the creation of MENADOC, an international market between the Maghreb, the Mashriq, and Subsaharan Africa for documentary film.

This year’s festival featured two Carte blanches: one to Nicolas Philibert and another to the Lebanese-born Rasha Salti, an esteemed film programmer of Arab and African film at the Toronto International Film Festival. Le Pays des sourds, Etre et avoir, Nénette, and La Maison de la radio offered a mini-retrospective of Philibert’s work. Unfortunately, the director and the public were disappointed by the amateurish screening facility at the Institut français. This is not intended as a jibe against that august institution, an important partner of the FIDADOC, but rather a sad and all too accurate reflection of the current state of cinemas–not just in the kingdom with a paltry 30 commercial screens currently in operation–but on the African continent as a whole.

Ironically, the Salem Cinema, was one of the only buildings to emerge unscathed from Agadir’s catastrophic earthquake in 1960, and became a refuge for the homeless. On Monday night, local musicians performed to a screening of filmed images of Agadir prior to the earthquake.

Photo Credit: S. Shafto

Photo Credit: S. Shafto

In Agadir there are currently projects to restore the Salem and the Sahara cinemas. In addition, during the FIDADOC, a representative from Burkino Faso was on hand to fund raise for the Ciné Guimbi, a closed Burkinabé film theatre in Bobo-Dioulasso (population 600,000, zero cinemas). Let’s hope that there will be a groundswell in such initiatives. The in-competition films were screened this year at the Hôtel de Ville, opposite a plaque commemorating King Mohamed V’s commitment to rebuild Agadir, after the earthquake.

Photo Credit: S. Shafto

Mohamed V’s inscription: “Destroyed by destiny, Agadir will be rebuilt by our will and our faith.” Photos: S. Shafto

I hadn’t seen Nicolas Philibert’s Le Pays des sourds/In the Land of the Deaf (1992), since showing it at the Bijou Cinema during my graduate student days at The University of Iowa in the mid 1990s. In introducing the film, the director said he was inspired to make the film after taking a class in sign language. The class made him realize that it was indeed a real language, full of nuance and depth. Sign language is also, he added, a visual language whose expressiveness and shot, counter-shot lend themselves to being filmed. Philibert’s non-miserabilist, humanist approach to filming his subjects (“I wanted to overturn the sad image of deaf persons.”) is remarkable.

It was also a pleasure re-visit the one-class village school, made up of 11 children from 3 to 12, in the Auvergne hamlet of Saint-Etienne-sur-Usson, population 250, that Philibert films in Etre et avoir/To Be and To Have (2002). Contemporary life is increasingly segregated by age groups. What interested the filmmaker in this one-room school, he told us, was showing the social benefits of interacting with persons of different ages.

Starting in January, he shot the film with a single camera over ten weeks, shooting approximately 35 minutes a day for a total of roughly 7 hours of rushes. Philibert, who is also behind the camera and thus knows his images well, has been editing his own films since his 1995 film La Moindre des choses. Some filmmakers prefer an abundance of rushes. Philibert, on the other hand, is already editing in the shoot.

The edit of To Be and To Have took the director five months. He began backwards, because he wanted to end with the last day of school. Finding the beginning of the film, he admitted, was more difficult: he didn’t want to start immediately in the classroom. Instead, To Be and To Have opens on an Auvergne landscape. As the credits roll, we hear the wind blow until the image track reveals a couple herding a troop of frightened cows during a winter storm. It’s a nice metaphor for the film and education (from the Latin e- ducere, to lead out) in general. A little later at the end of a school day, two turtles in the classroom suggest an allegory, à la Jean de la Fontaine, for the virtues of slowness and wisdom.

In the Land of the Deaf already revealed Philibert’s interest in sound and image. His most recent opus, La Maison de la radio (2012), celebrates listening by showing the faces of many of the French stars of the various national radio channels: whose 5,000 employees are housed in the circular building on the Avenue du Président Kennedy in Paris. In the cinema, we speak of photogenic individuals whom the camera loves. . . . Philibert’s film reminds us that the concept of photogéniealso exists for the human voice. The French politician Aristide Briand (1862-1932), for example, was described as having a voice like a cello, says my friend Jean-Claude.

As a long-time fan of France Culture, I appreciated the scene with Alain Veinstein. He possesses one of the most mellifluous voices on French radio. I liked it, too, because of Veinstein’s poignant encounter with the novelist, Bénédicte Heim on his late-night program, Du Jour au lendemain. When the news and even films (Laurent Cantet’s 2008 Entre les murs comes to mind) repeatedly focus on mistreated teachers and the failure of our schools, how refreshing to hear Bénédicte Heim talk about having been “touched by the grace” of her students in her book, Salle 113: une année scolaire en état de grâce. Despite the judicial notoriety that engulfed To Be and To Have for several years, this grace is also evident in the relation between the teacher, Georges Lopez, and his multi-age charges.

Georges Lopez with Jojo in To Be and To Have

If Philibert dismissed the word “master class” for its pretention, his generous 2-hour dialogue with the public was nonetheless highly instructive. Born in 1951, the filmmaker talked about his early years in Grenoble. Growing up without a television in a city he described as a “cultural desert,” Philibert remembered his parents’ cultural engagement: his father led discussions in a ciné-club in the late 60s and early 70s before film studies existed in French universities. It was by participating in those screenings as a teenager that Philibert began to conceive of film-making as a way to reflect upon the world. “I discovered the world, he told us, by watching films.” After working as an assistant to filmmaker René Allio, Philibert debuted with the militant documentary, La Voix de son maître/His Master’s Voice (1978). That film, co-directed with Gérard Mordillat, offers a fascinating x-ray of twelve French bosses of big business. The leaders of L’Oréal, IBM et al. are filmed frontally, in front of the camera, within an ample depth of field. Avoiding journalistic cuts, the filmmakers’ self-imposed brief was to analyze “how power invests words and language.” While making this film, Philibert realized documentary film-making was not a minor genre. In preparation for the shoot, Philibert and Mordillat didn’t read books on the economy. Rather they honed their gaze by studying the photography of Walker Evans: “The critical dimension in film," he said, "comes from the framing.”

Quoting Agnès Varda (“Chance is my best assistant.”), Philibert spoke eloquently about his own modus operandi. If he knows too much at the outset of making a documentary, his desire evaporates: “The less I know the better.” He discovers the film in the making. Forty years ago, filmmaking was considerably less bureaucratic: he received the Avances sur recettes for La Voix de son maître with just a 3-page dossier. He added–rightly it seems to me–that the copious dossiers required today to secure financing kills a certain creativity.

Mother and Daughter, Rabha with her little girl. Photo: Deborah Perkin

The in-competition part of the festival kicked off on Tuesday night with a screening of the British documentary Bastards by former BBC director, Deborah Perkin. For the past four years, Perkin has devoted herself to telling the tragic story of a courageous young Moroccan woman, Rabha. Forced into marriage at the age of 14 with a mute cousin she didn’t know, she became a mother at sixteen. A year later, she returned to her parents, unable to withstand her husband’s abuse. In trying to register her little girl, Rabha begins to understand the scope of her dilemma. Her traditional, fatwha marriage, she learns, has no legal status: her child is a “bastard.” Despite some positive advances in the Mudawana or Moroccan family law in 2004, when the legal age for marriage was raised to 18 for men and women (although a female can still be married at 15, with the consent of her parents), much remains to be done.

If in the West the stain of illegitimacy has subsided, such is not the case here in Morocco, where illegitimate persons continue to be treated as social pariah. Rabha realizes only too well the negative, lifelong effects on her daughter if considered a “bastard.” Unfortunately, Rabha’s innumerable hurdles are compounded by the fact she’s illiterate; her own parents didn’t send her to school. But through her unwavering belief in her right to a better future, and thanks to the fortuitous help of a tenacious social worker in Casablanca and a gifted human rights lawyer, Lamia Farida, Rabha takes on the law. . . . and ultimately wins. Perkin told me that her desire was to make a film about the law.

Rabha’s fight for herself and her daughter certainly resonates with the recent abominable kidnapping of the high school girls by Boko Haram (whose name literally means, education or books are forbidden) in Nigeria. . . . Deborah Perkin deserves kudos for her perseverance in making this film, as does Reda Benjelloun for having screened it on 2 – M, several days after the Agadir premiere. New Yorkers had a chance to see it too: Mahen Bonetti just screened it at the New York African Film Festival.

In one of the discussions, the Moroccan critic Mohamed Bakrim quoted Hitchcock’s famous line: “ Fiction is the work of the filmmaker. Documentary of God.” Of course, it could be easily argued that Hitchcock practiced filmmaking like a God, leaving little to chance. Meanwhile, the once firm boundaries between fiction and documentary have become increasingly porous. A few years ago, Jean-Pierre Rehm, the Artistic Director of the Marseille documentary film festival (FIDMaresille), decided, for instance, to accept fiction films in the festival.

Certainly one of the FIDADOC’s many forces is its pulse-taking of the world via divergent documentarian styles. One of the questions raised in documentary filmmaking is the relation between filmer and filmed. Deborah Perkin, on the one hand, subscribes to observational, “fly-on-the-wall” kind of documentary filmmaking that never tries to influence the action in front of the camera. Her style evokes Rossellini’s celebrated phrase: “Things are there, why manipulate them.” A purist, Perkin eschews on-camera interviews. She points to the films of British documentarian Kim Longinotti (Divorce Iranian Style, 1998) as an important influence. Nicolas Philibert, on the other hand, comes from a very different approach. And indeed in his films, we are occasionally conscious of individuals looking at the camera, as Axel does inTo Be and To Have:

"I don’t make myself invisible. That’s not what it’s about. It’s about making oneself accepted while filming. [. . .] In another words, act as if I’m there."

So it is only fitting that at one point in In the Land of the Deaf, the perch falls into the frame!

Nicolas Philibert with FIDADOC Director, Hicham Falah. Photo: S. Shafto

During the q and a, one audience member asked Philibert what he thought of the current trend to mix genres in documentary filmmaking. Philibert responded:

"A documentary is fiction. It’s another way of making a fiction film. It’s your vision that shapes the material and decides on where to place the camera. If ten directors make a film on the same subject, you will have ten different films. [. . .] A documentary is not a photocopy of the real. It’s rather a re-reading of the real. [. . . ] I often invent persons for my films. . . And then I find them."

Clearly, Philibert positions himself in the well-established French tradition of auteur filmmaking. And seeing his films together, certain leitmotifs began to appear: his fondness, for example, for one subject in each film as an alter ego, Florent in In the Land of the Dead, Jojo inTo Be and To Have. It’s clear too that he’s a master.

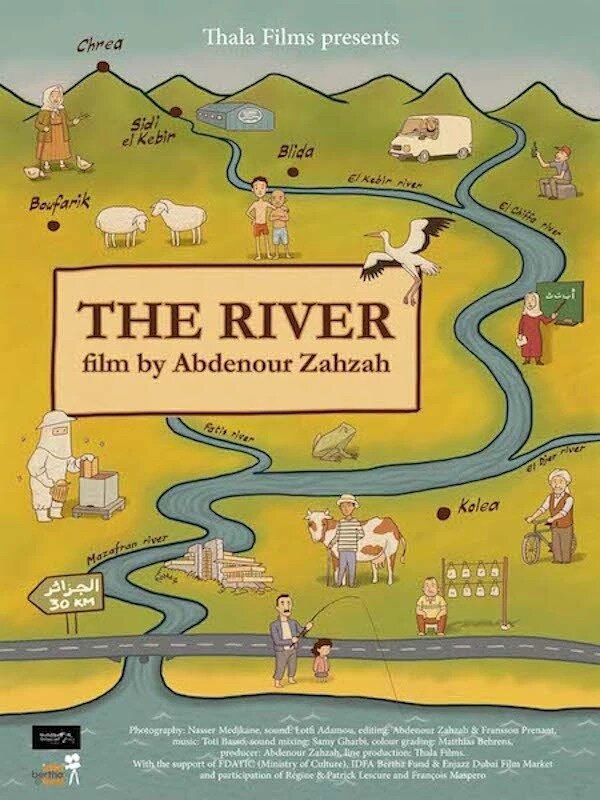

This year’s FIDADOC carried a large number of films from the Maghreb and the Mashriq. I was pleased, for instance, to discover Abdenour Zahzah’s new film, a documentary entitled El Oued, l’oued/The River, literally meaning along the river. I first heard of this filmmaker in watching Mounia Meddour’s documentary about young Algerain filmmakers (Le Cinéma algérien: un nouveau souffle, 2012), which includes a clip from Zahzah’s compelling short “Garagouz” (Marionettes). A road movie about a marionettist and his son as they travel about Algeria, “Garagouz” won twenty prizes on the international festival circuit.

Zahzah’s new film is also a road movie, this time a documentary. The River portrays Algerians living by the El Kebir River whom the director (he remains off-screen both on the image and sound tracks) encounters as he walks its 60 kilometer length, from high up in the Atlas mountains, down to its mouth at the Mediterranean. The scenery is often breathtaking, but the personal narratives that touch on the French occupation, the Franco-Algerian War, and the civil war in the 1990s are often heart-breaking. With these micro-territories, Abdenour depicts contemporary Algeria. Shown last year at IDFA (International Documentary Festival of Amsterdam), The River has already picked up several awards, including one for Best Artistic Work at the Luxor African Film Festival.

Several films by women stood out in the 2014 FIDADOC. Notably, Zeina Daccache’s Scheherazade’s Diary (Lebanon), winner of the FIDADOC’s Human Rights Award. It tells the story of women engaged in theatre as therapy in prison. Many of them are imprisoned for crimes they didn’t commit; while, unbelievably, one young woman is there for having worn her brother’s pants and ridden a bicycle. Present on the voice-over, the director has created a powerful film.

The Moroccan director Dalila Ennadre is also present in the voice-over of her film Des murs et des hommes/Walls and People, as she questions several inhabitants of the Casablanca medina. Like Zahzah’s The River, Walls and People is a damning portrait of the status quo made up of grinding, inescapable poverty that is the fate of so many in today’s Maghreb. If the medina’s walls were originally meant to be protective, they also imprison those who live there. One young man bitterly comments:

“To be born here is to be still-born. [. . .] Today, it is easier to go to heaven than to immigrate to Europe.”

Walls and People picked up the 2 - M prize. Walls and People and The River brings to my mind Nabil Ayouch’s hard-hitting Chevaux de dieu/Horses of God, a fiction film based on the true story of the young men responsible for the Casablanca bombings in 2003. With seemingly no way out of their shantytown, they opted for a one-way ticket to paradise. (Ayouch’s film has just opened at the Film Forum in New York.)

Another film that made its mark at this year’s year FIDADOC was Ne me quitte pas by Dutch filmmakers Niels van Koevorden and Sabine Lubbe Bakker. Originally, they wanted to make a documentary about the fraught political situation in Belgium, a country that set a Guinness world record in modern history when it was sans government for 535 days. They enlisted two friends from opposite sides of the political spectrum: the Flamand Bob and his francophone friend, Marcel.

A crisis on the set, however, prompted the filmmakers to change course following a suicide attempt by Marcel. His life rapidly devolved in a downward spiral after his wife left him for another man. Ne me quitte pas is about the friendship between Marcel and Bob, separated by roughly twenty years in age, and their mutual dependence on the bottle. In the end, realizing he’s headed to an early grave, Marcel checks himself into a clinic. Until then Bob has been in the background, seemingly more in control of his life. He becomes distraught when his son doesn’t show up for a scheduled meeting. If the film stresses the problems in alcohol addiction, it also suggests the fragility of men in the 21st century. Ne me quitte pas recently won an award at the Tribeca Film Festival and the Special Jury Prize at the FIDADOC.

Rasha Salti with filmmakers Jamal Khalaile, left, and Ahmed Ghossein, right. Photo: S. Shafto

I have spent the lion’s share of this review discussing Nicolas Philibert’s Carte blanche and master class. Rasha Salti’s was no less engaging. One of the films she programmed, the short–My Father is Still a Communist (2011, 31 mins.) by the Lebanese filmmaker Ahmed Ghossein–was a favorite. Ghossein composed his intimate film using family archives; it is narrated by excerpts from the audio tapes that his mother sent to his father during his 15-year stay in Saudia Arabia. Initially, I thought the film would echo Asmae El Moudir’s personal documentary about her uncle Merzouk and his fervent Stalinism: Souvenirs anachroniques.[1] But in My Father is Still a Communist, the eponymous father remains off-screen and there’s no mention of Communism . . . The film is more a poetic reflection on an absent paterfamilias and the daily trials endured by his family.

Still from “My Father is Still a Communist”

In the q and a, the filmmaker described the film as the “the image of a hero-father who is absent.” As a child, Ghossein thought his father was a Communist fighting against the Israelis. The reality, he later learned, was more mundane: his father was in exile to feed his family, unable to do so during the Lebanese Civil War. But surely that makes him a hero? My Father is Still a Communist was originally conceived as an installation for the Sharjah Bienniale: It was Rasha Salti who encouraged Ghossein to make a film. I’m waiting for part 2, where Ghossein gives us the reverse shot, told from his father’s perspective.

Another remarkable film in Rasha’s Carte blanche was My Love Awaits me by the Sea by Mais Darwazah, a young Palestinian filmmaker living in Jordan. Like most of the films in Rasha’s selection, it’s a personal film about the meaning of home for Palestinians (a subject that hits close to home for Salti whose grandfather, she told us, was a religious figure in Jerusalem): “When your place is seized, Mais tells us in her voice-over, your home is everywhere.” Her film is composed of footage but also of the filmmaker’s own animated drawings.

In her Master Class, Salti spoke of the first, direct images we saw during the Arab spring, usually on the nightly news. Such reportages don’t engage her. As a programmer, what interests are Arab filmmakers with a personal vision, those struggling with a strong self-censorship. She remarked that Beirut is a city that has been often filmed but that for the first time she actually recognized her home town in the film Birds of September, also in her programme, shot by the Lebanese television editor, Sarah Francis.

Like Nicolas Philibert, Rasha likes a mix of genres in documentaries: “Hybridity often makes for more interesting films.” The films in her programme could be called experimental or avant-garde. Jonas Mekas would surely have liked her Carte blanche! But the programmer herself prefers to call them creative or poetic documentary, because of the negative connotations of the word “experimental,” which, she told us, often sends an audience running in the opposite direction.

Every year she programs 7 Arab films for the Toronto Film Festival, which showcases 300 films. Statistically, 7 out of 300 doesn’t seem like much. It’s worth emphasizing, however, that such a spotlight on Arab film exists neither at Cannes nor at the Berlin Film Festivals. Single-handedly, Rasha is helping Arab films and filmmakers reach larger audiences.

After all these good films, my reader may think that’s it. But one of the best was saved for last. Going into the film, had the jury already more or less made their choices? No doubt. But the Congolese filmmaker Dieudo Hamadi’s exceptional Examen d’état (co-produced by Agat Films in Paris) swept away the competition and imposed itself as this year’s Grand Prix Nouzha Drissi.

It’s the story of a group of high school students in Kisangani, the filmmaker’s hometown. They are preparing to pass the state exam, the equivalent of the French baccalauréat at the end of the year. The opening scene introduces the Athénée Royale High School, a reminder that the goddess Athena was associated with knowledge and wisdom. Several students are clearing water out from a classroom after a recent flood, while one of them sarcastically renames the school: “Athénée poubelle” (Garbage Athénée).

In the next scene, we meet our protagonist, a young man whose name we never learn. He works part-time in the market to finance his studies. From his accompanying voice-over, we learn that his parents are dead and he lives with his aunt. Attendance at the local high school is contingent upon paying bonuses to the teachers: those who have not paid are escorted out of school. Passing the exam is regarded as the sine qua non for future success. The protagonist joins a group of rebel students, unable to pay the fees. They set up house in an unfinished building where they plan to study. Dieudo documents their often outlandish, extra-curricular efforts at exam preparation: consulting a marabout and bathing with special water, talking to the ancestors, having one’s bic pen blessed, and of course having recourse to someone who promises them the right answers. It’s impossible, he tells the students, to pass without cheating.

In the end, many students pass, by hook or by crook, the exam. But what Dieudo Hamadi couldn’t know at the outset is that his likable hero, despite his best efforts and his incantatory recital (“All my undertakings must be crowned with success, success, success, success. . . . I want to pass the State Exam!”), sadly fails. By not identifying him by name, Dieudo elevates hi m to the position of an Everyman in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Examen d’état is an exceptional documentary. Earlier this spring, it picked up two awards at the Cinéma du réel festival in Paris. In order to gain the students’ confidence, Dieudo Hamidi spent two months with them before picking up a camera. Over four months, he filmed 60 hours of rushes. His goal, he said, was “to film the things that are blocking my people: the corruption, the poverty that keep us enmeshed in a vicious circle.” The filmmaker himself comes from a scientific background, having studied to be a doctor. Although Dieudo completed various short-term, filmmaking programs, including La fémis’ summer school, it’s clear his talent is very much his own. He too is in a state of grace.

All translations from the French are by the author.

My thanks to El Mehdi Bahou for alerting me to the special dossier on Nicolas Philibert in the review Images documentaires, nos. 45/46 (2002). Available online at:

HTTP://WWW.IMAGESDOCUMENTAIRES.FR/NICOLAS-PHILIBERT.HTML

For more on this year’s FIDADOC, please consult its website:

HTTP://WWW.FIDADOC.ORG/CATEGORY/FIDADOC-2014

NOTES

[1]See my review of Asmae El Moudir’s film:

FIFTEEN AND COUNTING 15TH MOROCCAN NATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL, 2014

BIOGRAPHY

Since her arrival in Morocco in 2010, Sally Shafto has been regularly covering Moroccan and Maghrebin film. She is the author of theZanzibar Films and the Dandies of May 1968 (2007) and numerous articles on the French New Wave. She teaches at the Faculté Polydisciplinaire de Ouarzazate.